Questioning the link between citrus fruit and skin cancer

Source: PLOS.org, July 2015

A research article titled ‘Citrus Consumption and Risk of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma’ was just published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (1). You may have seen the several news headlines associated with the research. It caught my eye, as this relationship was news to me. Given that the results of the research would add a caveat to current cancer prevention recommendations, which encourage 5 or more servings per day of fruits and vegetables, it is worthwhile to break the study down.

The biological rationale for citrus fruits and malignant melanoma

Source: PLOS.com

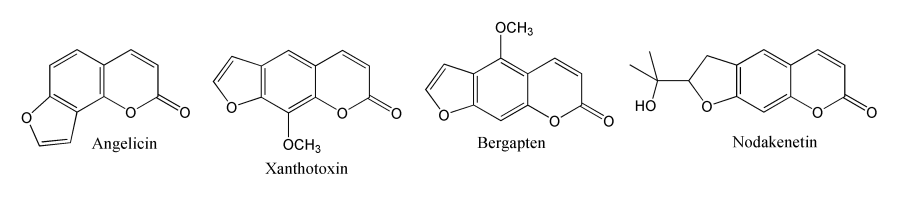

Citrus fruits are high in psoralens, which are a group of naturally occurring chemical compounds called furanocoumarins. Furanocoumarins are the compounds that cause grapefruit to adversely interact with several medications in the gut (this is why grapefruit is not served in hospitals). Furanocoumarins increase skin photosensitivity when applied topically to the skin and also when taken orally. For example, they are used in combination with UVA light to treat psoriasis. Psoralens also used to be used in tanning creams to enhance tanning.

So, although the idea may not be readily apparent to many, the authors of the study didn’t pull the idea of out thin air. The biological rationale is legitimate and worthy of investigation. They had done previous research looking at antioxidant nutrients and melanoma risk, and had found that women with a higher intake of orange juice and dietary vitamin C unexpectedly had an increased risk for melanoma, while this effect was not apparent in women who only took supplementary vitamin C (1). The authors then hypothesised that some other compound present in foods containing vitamin C (i.e. citrus fruits) must be responsible for the increased melanoma risk they observed (1). Psoralens were a compound that made biological sense, and this study was born.

What did they do?

Prospective data came from 63,810 women in the U.S. Nurses’ Health Study and 49,617 men in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. The study began in 1984 for the women and 1986 for the men, where both groups filled out a ‘baseline’ questionnaire about their diet, along with providing other data such as medical history and other lifestyle risk factors. The study participants were followed forward to track any new diagnosis of malignant melanoma, and they filled out ‘follow-up’ questionnaires every two to four years. Each person was followed until one of three events occurred: first diagnosis of any new cancer, death, or end of the study in January 2010 (men) or June 2010 (women).

In the food frequency questionnaires, the study participants were asked how often, on average, they had consumed grapefruit (half), oranges (one), and grapefruit and orange juices (on small glass) in the past year. The total individual citrus fruit servings defined ‘overall citrus consumption’, the main exposure variable in the study. This variable was updated every two to four years to better reflect long-term dietary intake.

The researchers used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazards ratios for malignant melanoma according to frequency of consumption of:

a) overall citrus fruit

b) grapefruit

c) grapefruit juice

d) oranges

e) orange juice

The authors accounted for potential confounding variables in the analysis, meaning that the results are independent of these factors: age, family history of melanoma, natural hair colour, number of arm moles, sunburn susceptibility as child or adolescent, number lifetime blistering sunburns, cumulative ultraviolet flux since baseline, average time spent in direct sunlight since high school, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, and intake of total energy, alcohol, coffee, and vitamin C from supplements. Analyses for women also accounted for menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone therapy.

What did they find?

The risk of malignant melanoma increased with increasing overall citrus fruit consumption, in a ‘dose-response’ fashion (1).

Men and women who reported eating citrus fruits more than 1.5 times per day had a 36% increase in risk for malignant melanoma compared with people who ate citrus fruits less than twice per week.

Curiously, when the different types of citrus fruits were looked at individually, grapefruit and orange juice consumption were associated with increased melanoma risk, but grapefruit juice and oranges were not. The study authors have been met with some criticism about the consistency of the results across different types of citrus fruits and the small number of cases of malignant melanoma that the conclusions are based on (to be fair, it is a rare cancer).

What does it mean?

The lead author of the study, Shaowei Wu, a postdoctoral research fellow at Brown University, said in the press release,

“While our findings suggest that people who consume large amounts of whole grapefruit or orange juice may be at increased risk for melanoma, we need much more research before any concrete recommendations can be made.”

The authors conclude that the lack of associations they observed with oranges and grapefruit juice was because people ate less of them than they did of orange juice and grapefruits. Dubious? It’s hard to say, given that errors in the measurement of people’s actual consumption could also explain the results. People may make errors in recalling how often they ate citrus fruits in the past year, adding noise to the data. It has also been pointed out that the study participants were all health professionals, and so they may be better at detecting skin lesions indicative of melanoma than the general population (2).

My question is, how many people actually eat citrus fruits more than 1.5 times per day? Also, if the absolute lifetime risk of developing malignant melanoma is about 2.1% (2), then crudely calculated, a 36% relative increase in risk due to eating citrus fruits more than 1.5 times per day (assuming causality) would result in a lifetime risk of 2.9% for malignant melanoma. Because people’s baseline risk of malignant melanoma is relatively low, a 36% increase in relative risk does not mean as much as it would for a more common cancer, such as breast cancer.

Where do we go from here?

This study is an example of the kind of research that can lead to a lot of public confusion. People say that ‘everything causes cancer’, and it’s partly from reading headlines like the ones accompanying this study. It is difficult because there might be a public health relevance to the findings – if eating citrus fruits increases cancer risk to a significant degree, then the public should know. But, it’s hard to know what to do when we also know that citrus fruits are a key source of vitamin C and count towards daily servings of fruit and vegetables. As Marion Nestle said, ‘I’d worry much more about alcohol and cigarettes‘ (3). It will be interesting to see if the results of this research are replicated in other studies.

References

1) Wu S, Han J, Feskanich D, Cho E, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Qureshi AA. Citrus consumption and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4111

2) Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html (accessed 11 July 2015).

3) Eunjung Cha A. Citrus consumption and skin cancer: how real is the link? Washington Post. 29 June 2015. http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2015/06/29/citrus-consumption-and-melanoma-how-real-is-the-link/ (accessed 11 July 2015).