What molecular changes drive metastasis in melanoma?

When a melanoma that appears for the first time is localized and excised, it presents a low risk for the patient. But when this tumour decides to travel and deposit itself somewhere else in the body, it becomes a dangerous situation.

While the events that make melanoma appear for the first time have been fairly characterized, those that make it metastasize to distant organs of the body such as the liver, lungs and brain are less understood. An important reason for this is the difficulty in accessing tumours from distant metastatic sites. At PeterMac, a rapid autopsy program was implemented that allows for the acquisition of such tissue samples with the consent of the patients and their families. This provides a unique opportunity to investigate the key events that drive metastasis by comparing the metastatic samples to the primary melanoma tumour of the same patient.

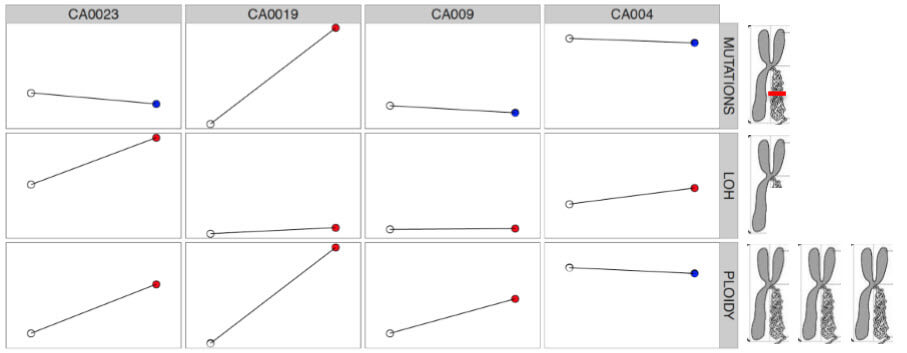

Figure 1. Three key events analysed across four cases. Each column represents a case (patient) and each row represents an event. The impact of each event is shown on a drawing of a chromosome, of which we each have originally 23 pairs. For each event, the overall amount in the metastases can decrease (in blue) or increase (in red) compared to the original site of the melanoma.

These “events” we refer to occur in the DNA of tumour cells (Figure 1). The DNA is a long string of characters (A, C, T and G) carried by 23 pairs of chromosomes inherited from our parents, one copy each. And along these chromosomes there are encoded genes, which are words that are read and turned into proteins – the workers of the cell!

The first type of event we looked at is one of the smallest that can occur in the DNA and it refers to single point mutations – changing one letter for another in a gene. We observe that for most patients, the number of single point mutations in the metastases is not much more than those in the primary tumour.

A second type of event refers to the partial or total loss of a part of a chromosome, this is, deleting one or more genes at once! We observe an accumulation of these changes in metastasis, but different patients acquire these to a different extent: some of them lose a few genes, other lose many.

A third type of molecular change affects the total amount of chromosomes (or large parts of these) in the tumour. What we observe is that this amount tends to increase heavily in patients –despite the deleted genes described above! – in the metastasis.

Once we get a good idea of how metastasis looks like, we can detect its presence in earlier stages – for example in the primary tumour excised or in subsequent blood samples. And by associating its presence to clinical variables, we can determine if it confers a poorer prognosis for the patient.